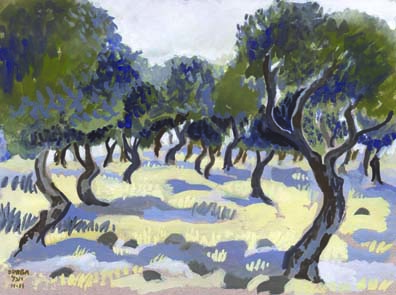

Study of olive grove, Kaditah, northern Israel - (all artwork © Durga Yael Bernhard - do not reproduce)

A Picture Book Creates Its Author

Sometimes authors and illustrators don’t pick the subjects of their books. Sometimes the subjects pick them. Five years ago, I had no particular interest in olives. Then the idea for a book about an ancient olive tree took root in my psyche, and has been growing ever since.

This will not be my first book about a tree. In 2000, I wrote and illustrated Earth, Sky, Wet, Dry: A Book of Nature Opposites (published by Orchard Books; later republished in Korea). This book grew out of the desire to paint illustrations from the natural world around my home. The fields and orchards where I lived along the Hudson River were bucolic and sunny, and made a lovely setting for a book. I discovered the joy of illustrating a winter scene directly from my own window on a snowy day, or painting wildflowers from the nearby woods to include in the book. My main subject was a pear tree from a nearby orchard – and all the flora and fauna that exist in the world of a single tree. It didn’t have to be a pear tree; any fruit tree would have served just as well.

Not so with the olive tree. This time, the tree provided the seed, and the book has grown from there. And just as the olive tree, with its unique gifts and long-reaching lifespan, has helped shaped human history for hundreds of centuries, it is having a shaping effect upon my life, too. Like a pregnant woman who craves new foods her body knows it needs, in order to research this book I have found myself drawn to learn things that never would have interested me before. I had the great good fortune to travel to Israel twice to visit ancient olive groves in the Galilee, and modern ones near Tel Aviv. I talked with olive farmers and photographed olive presses with ancient grinding stones, and modern ones equipped with stainless steel centrifuges. I read about the history of olives, how olive presses have developed over the centuries, and about the present-day olive oil industry. Did you know that green olives are unripe black olives? Did you know that the black olives sold in cans in American supermarkets are not really black? Did you know most Italian olive oil comes from Spain? Did you know “extra virgin” refers to the acid content in the oil? I didn’t, before I started working on this book. And there is so much more to learn.

This book is not just about trees. It’s about people. It’s about culture and tradition. It’s about history, conquest, and peace. It’s about food and farming, trade and technology. Olive trees encompass all of these subjects and more. The oil has annointed kings and is burned for light, miraculously sustained for eight nights in the story of Chanukah. The dried “mash” of fiber and pits that are left behind after pressing is burned for fuel. Charcoal from olive pits has been found in Jericho dating back ten thousand years. And just as the trunks and limbs of these hardy fruit trees are sculpted by time into unique shapes, the wood of the olive tree has long been carved into bowls, spoons, and other objects.

The drawings and paintings you see here are some of my studies of olive trees and the environments in which they live. I worked on site in pencil, and I took photographs from which to paint at home.  Here you see a portrait I did of the gnarled and sculpted bark of one particular tree in the Garden of Gethsemane, where legend holds that Jesus of Nazareth spent his last night before being arrested by Roman soldiers and made to carry a cross of olive wood up the Via Dolorosa. Even before the Roman conquest of the Holy Land, the olive tree was a symbol of resurrection due to its miraculous regenerative powers. This tree was alive then, and you can still see new growth sprouting from its ancient bark. It is said that if an olive tree could talk, it would say, “Make me poor, and I’ll make you rich”, because hacking away at the tree makes it produce abundant fruit. Olives are uniquely dependent upon humans, not just to unlock the nutritious treasures of its bitter fruit, but to keep the trees pruned, without which they cannot live very long. A tree that is properly pruned can live for thousands of years, constantly regenerating itself even as the older parts of the tree die.

Here you see a portrait I did of the gnarled and sculpted bark of one particular tree in the Garden of Gethsemane, where legend holds that Jesus of Nazareth spent his last night before being arrested by Roman soldiers and made to carry a cross of olive wood up the Via Dolorosa. Even before the Roman conquest of the Holy Land, the olive tree was a symbol of resurrection due to its miraculous regenerative powers. This tree was alive then, and you can still see new growth sprouting from its ancient bark. It is said that if an olive tree could talk, it would say, “Make me poor, and I’ll make you rich”, because hacking away at the tree makes it produce abundant fruit. Olives are uniquely dependent upon humans, not just to unlock the nutritious treasures of its bitter fruit, but to keep the trees pruned, without which they cannot live very long. A tree that is properly pruned can live for thousands of years, constantly regenerating itself even as the older parts of the tree die.

As I write this post, the olive harvest is winding down all over the Middle East. Israelis and Palestinians are taking their newly-picked olives to community presses, where techniques for curing and pressing, packaging and preserving are debated endlessly. Like the land in which they grow, olives are a rich and complex subject, and the debate is often lively, and – despite what international headlines would have us believe – quite friendly. Some of those presses are shared, as people travel back and forth across physical and cultural boundaries to get their olives pressed. Olives, true to legend, do foster peace. For olive-loving folk, the press is a place of common ground.

Further north in Greece, France, Italy, and Spain, the harvest goes later. With a little luck, I’ll be picking olives in one of these places next autumn. What’s a year, in the lifespan of an olive tree? In the meantime, my heart is with the harvest as I follow news of the olives from afar.

I can’t wait to weave everything I’ve learned about olive trees into my future book. Some books take a long time to ripen – but like well-seasoned wine or perfectly-blended oil, it’s well worth the wait.

2 Responses to Olives from Afar